“Never before has any voice dared to utter words of that tongue in Imladris, Gandalf the Grey,” said Elrond, as the shadow passed.

“And let us hope that none will ever speak it here again,” answered Gandalf.

At the beginning of the Fellowship, Gandalf refuses to utter words in the Black Speech. Even at the climax of his first conversation with Frodo regarding the Ring—when he throws it into the fire, revealing the spidery lines of Elvish-looking script—Gandalf does not read the inscription on the Ring aloud.

“The language is that of Mordor,” he tells Frodo, “which I will not utter here.” And Gandalf proceeds to give an English translation of the inscription, a translation which is now familiar to Tolkien fans everywhere:

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them . . .

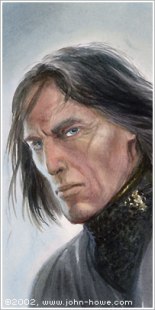

At the Council of Elrond, however, the situation is different. Gandalf is nearing the climax of a very different conversation. He is presenting evidence to a councilful of people regarding (1) the identity of the One Ring and (2) the seriousness of the situation. And at the climax of that conversation, we find Gandalf thundering out the language of Morder:

Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul . . .

The mighty tremble, and the Elves stop their ears.

Why speak those unspeakable words? Why speak them in the Council but not in Frodo’s living room?

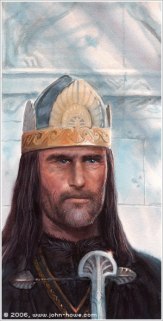

Gandalf achieves at least three excellent effects by uttering those words at the Council. First, and most immediately, they serve to establish the identity of the One Ring. Exactly the correct words appear on the Ring’s inscription. Previously in Frodo’s living room, Gandalf softened the blow of this fact by reciting a translation; but in a council of Elves who know the Black Speech, the exact wording is important.

Second, those words establish the seriousness of the situation. “I do not ask your pardon,” Gandalf tells Elrond. The finding of the Ring means the Black Speech is “soon to be heard in every corner of the West”—and that is precisely why a solution must be found.

Third, Gandalf achieves something that Tolkien is a master at doing obliquely. He increases our fear of evil, not by portraying it directly, but by portraying it by negation. The words of the Black Speech are words which—in a subversion of wordhood itself—must not be spoken. They are unspeakables. The rule is underscored even in Gandalf’s breach of it. And this is part and parcel with Tolkien’s treatment of evil throughout the trilogy. We know Evil not by how it looks and sounds, but by how it doesn’t look or sound. It is silence and darkness—and that is well, because when it becomes even semi-audible and visible (as it does with the Ringwraiths, or with Gandalf’s uttering of the Black Speech), it cannot be endured.

And so Tolkien turns the screw of suspense in the Council. He increases the council members’ conviction that they have found the One Ring. And he increases our suspense over the central puzzle: what is to be done with this Ring, this unspeakable thing?

*As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

You must be logged in to post a comment.